We were both poorer and richer than today’s graduates, or: The Planet is dying!

Since this is

going to be quite a read—I tried to stick to 1,000 words, but that wasn’t

humanly possible—I now hand you the summary of what you’re about to read. I

guess that’s the best thing to do, since you probably have something very

important to do. In fact, more important than read my little text about being a

bit old.

In any case, in 1967, we had something we now refer to as The Summer Of Love—I know Partner is quite keen on that one, since it embraces Hippies, equality, art and music. In fact: love.

I don’t have the Hippie-mind like Partner—I chose the Punk route to create the thing I am today—but I do get that the idea was appealing.

Subsequently, The Summer of Love was a social phenomenon that occurred during the summer of 1967, when as many as 100,000 people, mostly young people sporting hippie fashions of dress and behavior, converged in San Francisco's neighborhood Haight-Ashbury. Although hippies also gathered in many other places in the U.S., Canada and Europe, San Francisco was at that time the most publicized location for hippie subculture.

Hippies, sometimes called flower children, were an eclectic group. Many were suspicious of the government, rejected consumerist values, and generally opposed the Vietnam War. A few were interested in politics; others were concerned more with art (music, painting, poetry in particular) or spiritual and meditative practices.

Inspired by the Beat Generation of authors of the 1950s, who had flourished in the North Beach area of San Francisco, those who gathered in Haight-Ashbury during 1967 allegedly rejected the conformist and materialist values of modern life; there was an emphasis on sharing and community. TheDiggers* established a Free Store, and a Free Clinic where medical treatment was provided.

The prelude to the Summer of Love was a celebration known as the Human Be-In* at Golden Gate Park on January 14, 1967, which was produced and organized by artist Michael Bowen.

Also at this event, Timothy Leary* voiced his phrase, "turn on, tune in, drop out". This phrase became the chisel for shaping the entire hippie counterculture, as it voiced the key ideas of 1960's rebellion. These ideas included communal living, political decentralization, and dropping out. The term "dropping out" became popular among many high school and college students, who would often abandon their education for a summer of sex, drugs, and rock n' roll.

In England, gatherings with a theme similar to that of the Summer of Love occurred in various places in London. The UFO Club in Tottenham Court Road, was a gathering place where psychedelic musical groups such as Pink Floyd and the Soft Machine played, accompanied by light shows. The 14 Hour Technicolor Dream in the Alexandra Palace was another major event, where amongst others, Pink Floyd, The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, Soft Machine, The Move, Tomorrow, and The Pretty Things played.

The music of this era fused dance beats with a psychedelic, 1960s flavor, and the dance culture drew parallels with the hedonism and freedom of the Summer of Love in San Francisco two decades earlier. Similarities with the Sixties included fashions such as Tie-dye. The smiley logo is synonymous with this period.

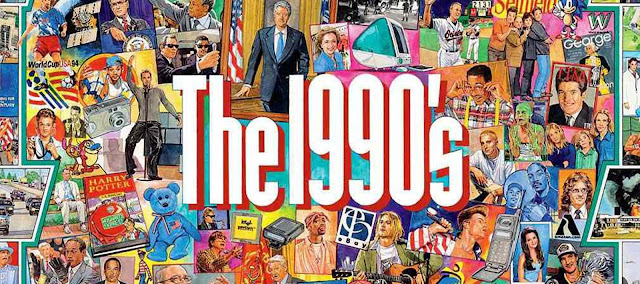

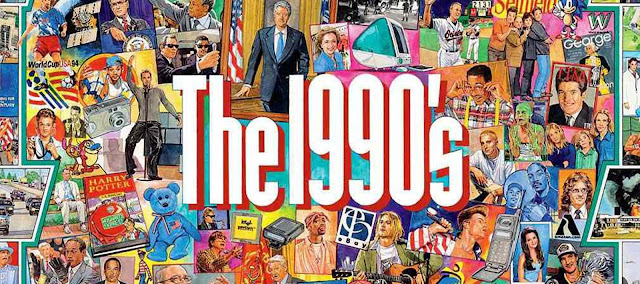

I’ve been thinking a lot about the Nineties recently. You know, in that slightly hazy, lens-flared Instagrammed way that people think about the Sixties.

Before you say “it’s my age”, it’s not – or at least not entirely. Let’s face it, nostalgia-wise, we’ve strip-mined the Eighties down to bedrock: there’s a Dynasty remake on Netflix, for God’s sake. It’s time to move on and start reminiscing about something new.

Anyway, what my little walks down memory lane have me thinking is that, actually, the Nineties were fantastic. And not just because I was 13-24, not 42 and sleep was optional. It was a great decade to be young. We had cool music. We had cool drugs. And sometimes, we even had cool politicians. We thought history had ended in a good way—mark the Cold War reference, or the 1989-thing; you know: The Wall. Anything seemed possible. Let me just put it this way: the Nineties were our Sixties.

I got a sneak preview of what the Nineties could be about, way back in 1990. I’d taken a Gap Year which, like most Gap Years back then, was taken entirely for kicks and with no notion of following a passion or becoming more attractive to universities or employers. And when I say Gap Year, I obviously mean, that I was partying a little too hard to pass at school, so I had to do the same year over again—study-wise. At the end of that flunked schoolyear, I happened to bump into a up-and-coming DJ in a record store—where I used to hang out all the time, spending my hard-earned money on whatever I could get my hands on—who told me about a new style of dance music he wanted to offer to the clubs.

A year later—passed the schoolyear positively, by the way—in 1991, I—as a young and upcoming artist—made a bit of a name in Amsterdam. The decade looked, at first glance, rather less promising than its predecessor.

In fact, being barely employed in the arts—and still a student on the side—in Amsterdam was fine back then, because property cost nothing. This bears repeating. You left your provincial background and went to stay with a friend who lived in Amsterdam while you performed your ass off in local dumps while looking for a flat. The question you asked yourself was, “Which part of The City—or the neighboring ‘burbs—do I want to live in while I look for a job that will provide for this lifestyle?”

Since the world was not only better then, it was also smaller. Most of us could walk to school and to work (and-more importantly—walk home at 4am when we’d finished clubbing). We had tiny commutes and living in places two hours by train from the city was considered eccentric and pointless. Also, you know all that crap estates agents spout about “urban villages”? Well, back then Amsterdam—including the ‘burbs—did feel quite like a village, because most of your friends lived within walking distance—and your neighbors were normal people, not workaholic bankers and sundry Poles. We were both poorer and richer than today’s graduates.

Our meagre outgoings and negligible work commitments meant that our careers came a very distant second to having fun. This was great as something big was happening in The Nineties in Europe. After decades of grey, post imperial decline our capitals were stirring. One of the early signs of this was the appearance of seriously stylish clubs. Where once clubs were grim rip-off joints with metropolitan pretensions and weird Seventies hangovers, they suddenly became the sort of places you found in New York. And I could get a whiff of all of them, since Partner had an acquired spot in the Nineties Rock Scene and my friend The Italian was quite fond of the entire dance scene that went on in Amsterdam. So one weekend I was dancing to this new music-thing called Grunge, the next I dosed away on Frankie Knuckles. In short, I dread to think what proportion of my late teens was spent in clubs, in the queue for clubs or waiting for taxis after the clubs.

Music had become cool. In fact, it was great—and what’s more it was ours. It was the last truly home-grown musical movement before the internet globalized youth culture forever. We had dance, rap and grunge and, of course, the Spice Girls, who now look like the most inexplicable period piece ever.

Great music requires great drugs and we had those too. Ecstasy and cocaine were everywhere—we drank loads and then did drugs so we could drink more. We sometimes went to work straight from the club as, for a while, clubbing on Sundays was quite the done thing. Monday morning downers and serotonin-sapped Suicide Tuesdays didn’t matter. You lived for weekends – and besides, in the Nineties, slacking was still cool. Nobody pretended they loved their job.

So, yes, Partner, The Italian and I went to a lot of parties and met an awful lot of famous people. In fact, it’s only since I’ve become old and boring that I’ve realized just how lucky I was. How lucky we all were.

It wasn’t just a cultural renaissance either. There was the political climate—Eighties governments slid towards its inevitable, sleazy, exhausted end and, later, that fantastic feeling of hope flew in. If I had to encapsulate the Nineties in a few lines, it would be the sunny morning after Hopeful Politics swept to power. I would probably have been walking to work, past squares where friends lived, humming some fantastic music, hungover from a party, but filled with the feeling that the world had become a better place. That feeling really was incredible—the most uncynical I’ve ever been about life.

Let’s see – what else? We had the start of the dot-com boom. We had magazines like Loaded and Viz. Films like Trainspotting. We had gender equality without today’s hair-trigger sensitivity and public shaming’s. Food was getting better but hadn’t yet become a tedious, all-encompassing obsession. Wages went up, not down. Global warming was a vague future threat—and nothing to do with your skiing holiday. Beards were short or non-existent. And, speaking of which, Islamist Terrorism was a mere twinkle in the largely unknown Osama Bin Laden’s eye...

In fact, unless the remaining of the 2010s have an incredible surprise up their sleeves, the Nineties will have been the best decade of the last 50 years. We had it so good.

Anyway, the

summary is this: “[…] it would be the sunny morning after Hopeful Politics

swept to power. I would probably have been walking to work, past squares where

friends lived, humming some fantastic music, hungover from a party, but filled

with the feeling that the world had become a better place.”

Now that we

got that out of our systems, let’s begin with the beginning:

nostalgia

nɒˈstaldʒə

noun: nostalgia; plural noun: nostalgias

* a sentimental longing or wistful affection for a period in the past.

"I was overcome with acute nostalgia for my days at university"|

synonyms:

| wistfulness, longing/yearning/pining for the past,

regret, regretfulness, reminiscence, remembrance, recollection, homesickness,

sentimentality

"there is a nostalgia for traditional

values"

|

* something done or presented in order to evoke feelings of nostalgia.

"an evening of TV nostalgia"

There. I

thought I just re-start with that.

And with

that thought I’d like to take you back to the year 1967—unlike what the above picture might suggest. So, 1967. Not that I was alive

back then—my parents were, however—but it’s the place to start my recent

rambling on the subject of nostalgia.

You see,

the world is dying. I think we all agree on that. And the more we loose of this

fantastic planet—not that I’ve actually seen other planets as a reference, but

who’s counting?—the more I think back to better times.In any case, in 1967, we had something we now refer to as The Summer Of Love—I know Partner is quite keen on that one, since it embraces Hippies, equality, art and music. In fact: love.

I don’t have the Hippie-mind like Partner—I chose the Punk route to create the thing I am today—but I do get that the idea was appealing.

Subsequently, The Summer of Love was a social phenomenon that occurred during the summer of 1967, when as many as 100,000 people, mostly young people sporting hippie fashions of dress and behavior, converged in San Francisco's neighborhood Haight-Ashbury. Although hippies also gathered in many other places in the U.S., Canada and Europe, San Francisco was at that time the most publicized location for hippie subculture.

Hippies, sometimes called flower children, were an eclectic group. Many were suspicious of the government, rejected consumerist values, and generally opposed the Vietnam War. A few were interested in politics; others were concerned more with art (music, painting, poetry in particular) or spiritual and meditative practices.

Inspired by the Beat Generation of authors of the 1950s, who had flourished in the North Beach area of San Francisco, those who gathered in Haight-Ashbury during 1967 allegedly rejected the conformist and materialist values of modern life; there was an emphasis on sharing and community. TheDiggers* established a Free Store, and a Free Clinic where medical treatment was provided.

The prelude to the Summer of Love was a celebration known as the Human Be-In* at Golden Gate Park on January 14, 1967, which was produced and organized by artist Michael Bowen.

Also at this event, Timothy Leary* voiced his phrase, "turn on, tune in, drop out". This phrase became the chisel for shaping the entire hippie counterculture, as it voiced the key ideas of 1960's rebellion. These ideas included communal living, political decentralization, and dropping out. The term "dropping out" became popular among many high school and college students, who would often abandon their education for a summer of sex, drugs, and rock n' roll.

In England, gatherings with a theme similar to that of the Summer of Love occurred in various places in London. The UFO Club in Tottenham Court Road, was a gathering place where psychedelic musical groups such as Pink Floyd and the Soft Machine played, accompanied by light shows. The 14 Hour Technicolor Dream in the Alexandra Palace was another major event, where amongst others, Pink Floyd, The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, Soft Machine, The Move, Tomorrow, and The Pretty Things played.

Now, obviously

England is key here, since it ultimately leads to The Second Summer Of Love.

The Second

Summer of Love is a name given to the period in 1988 and 1989 in the

UK, during the rise of acid house music and the euphoric explosion of

unlicensed MDMA-fueled rave parties. The term generally refers to the summers

of both 1988 and 1989 when electronic dance music and the prevalence of the

drug MDMA fueled an explosion in youth culture culminating in mass free parties

and the era of the rave. The music of this era fused dance beats with a psychedelic, 1960s flavor, and the dance culture drew parallels with the hedonism and freedom of the Summer of Love in San Francisco two decades earlier. Similarities with the Sixties included fashions such as Tie-dye. The smiley logo is synonymous with this period.

I’m not saying

that Nostalgia should come with a

smiley logo, or anything. Or a photo of The

Italian on some remote beach with his Walk-Man*.

However, ever

since I forcibly rode into my forties and in a way was forced to take on the

shape of Charlie in order to put things in perspective—as if that’s a

possibility, here—I long for a new Summer

Of Love. Preferably one that lasts as long as the Nineties, since that was

my personal, endless Summer Of Love.

You know, the peaceful Nineties, that started the day the Cold War

ended—1989—and ended when the War On Terror started—2001. A peaceful period in

the history of men, sandwiched between two warful periods—the latter still

ongoing.I’ve been thinking a lot about the Nineties recently. You know, in that slightly hazy, lens-flared Instagrammed way that people think about the Sixties.

Before you say “it’s my age”, it’s not – or at least not entirely. Let’s face it, nostalgia-wise, we’ve strip-mined the Eighties down to bedrock: there’s a Dynasty remake on Netflix, for God’s sake. It’s time to move on and start reminiscing about something new.

Anyway, what my little walks down memory lane have me thinking is that, actually, the Nineties were fantastic. And not just because I was 13-24, not 42 and sleep was optional. It was a great decade to be young. We had cool music. We had cool drugs. And sometimes, we even had cool politicians. We thought history had ended in a good way—mark the Cold War reference, or the 1989-thing; you know: The Wall. Anything seemed possible. Let me just put it this way: the Nineties were our Sixties.

I got a sneak preview of what the Nineties could be about, way back in 1990. I’d taken a Gap Year which, like most Gap Years back then, was taken entirely for kicks and with no notion of following a passion or becoming more attractive to universities or employers. And when I say Gap Year, I obviously mean, that I was partying a little too hard to pass at school, so I had to do the same year over again—study-wise. At the end of that flunked schoolyear, I happened to bump into a up-and-coming DJ in a record store—where I used to hang out all the time, spending my hard-earned money on whatever I could get my hands on—who told me about a new style of dance music he wanted to offer to the clubs.

A year later—passed the schoolyear positively, by the way—in 1991, I—as a young and upcoming artist—made a bit of a name in Amsterdam. The decade looked, at first glance, rather less promising than its predecessor.

In fact, being barely employed in the arts—and still a student on the side—in Amsterdam was fine back then, because property cost nothing. This bears repeating. You left your provincial background and went to stay with a friend who lived in Amsterdam while you performed your ass off in local dumps while looking for a flat. The question you asked yourself was, “Which part of The City—or the neighboring ‘burbs—do I want to live in while I look for a job that will provide for this lifestyle?”

Since the world was not only better then, it was also smaller. Most of us could walk to school and to work (and-more importantly—walk home at 4am when we’d finished clubbing). We had tiny commutes and living in places two hours by train from the city was considered eccentric and pointless. Also, you know all that crap estates agents spout about “urban villages”? Well, back then Amsterdam—including the ‘burbs—did feel quite like a village, because most of your friends lived within walking distance—and your neighbors were normal people, not workaholic bankers and sundry Poles. We were both poorer and richer than today’s graduates.

Our meagre outgoings and negligible work commitments meant that our careers came a very distant second to having fun. This was great as something big was happening in The Nineties in Europe. After decades of grey, post imperial decline our capitals were stirring. One of the early signs of this was the appearance of seriously stylish clubs. Where once clubs were grim rip-off joints with metropolitan pretensions and weird Seventies hangovers, they suddenly became the sort of places you found in New York. And I could get a whiff of all of them, since Partner had an acquired spot in the Nineties Rock Scene and my friend The Italian was quite fond of the entire dance scene that went on in Amsterdam. So one weekend I was dancing to this new music-thing called Grunge, the next I dosed away on Frankie Knuckles. In short, I dread to think what proportion of my late teens was spent in clubs, in the queue for clubs or waiting for taxis after the clubs.

Music had become cool. In fact, it was great—and what’s more it was ours. It was the last truly home-grown musical movement before the internet globalized youth culture forever. We had dance, rap and grunge and, of course, the Spice Girls, who now look like the most inexplicable period piece ever.

Great music requires great drugs and we had those too. Ecstasy and cocaine were everywhere—we drank loads and then did drugs so we could drink more. We sometimes went to work straight from the club as, for a while, clubbing on Sundays was quite the done thing. Monday morning downers and serotonin-sapped Suicide Tuesdays didn’t matter. You lived for weekends – and besides, in the Nineties, slacking was still cool. Nobody pretended they loved their job.

It wasn’t just

about hedonism, though. There was genuine optimism in the air. The Eastern Bloc

had crumbled and the good guys had won. This meant a sudden influx of exciting,

exotic new people. Hell, my music career even took off big time in Russia,

which makes me realize just how grim the former Soviet Union must have been.

But it also

points to a nice thing about Nineties Europe. It was strangely egalitarian. We

didn’t yet have cities where the super-rich had turned the best bits into a

socially cleansed VIP section. You went to bars and clubs and pubs and you met

famous people all the time. Obviously, back then as a celeb—or, more to the

point: this weird Punk Hero—myself I sort of lost count of the number other—more

established—celebrities and movers and shakers I bumped into, usually half cut,

in the Nineties. It was a bit like being a drunk Forrest Gump. And they—we—were

there for everybody to meet. It was a “I saw you in Whatever and think you’re great! Have a beer on

me” situation, all year—decade—round.So, yes, Partner, The Italian and I went to a lot of parties and met an awful lot of famous people. In fact, it’s only since I’ve become old and boring that I’ve realized just how lucky I was. How lucky we all were.

It wasn’t just a cultural renaissance either. There was the political climate—Eighties governments slid towards its inevitable, sleazy, exhausted end and, later, that fantastic feeling of hope flew in. If I had to encapsulate the Nineties in a few lines, it would be the sunny morning after Hopeful Politics swept to power. I would probably have been walking to work, past squares where friends lived, humming some fantastic music, hungover from a party, but filled with the feeling that the world had become a better place. That feeling really was incredible—the most uncynical I’ve ever been about life.

Let’s see – what else? We had the start of the dot-com boom. We had magazines like Loaded and Viz. Films like Trainspotting. We had gender equality without today’s hair-trigger sensitivity and public shaming’s. Food was getting better but hadn’t yet become a tedious, all-encompassing obsession. Wages went up, not down. Global warming was a vague future threat—and nothing to do with your skiing holiday. Beards were short or non-existent. And, speaking of which, Islamist Terrorism was a mere twinkle in the largely unknown Osama Bin Laden’s eye...

Of course, inevitably,

it went bad. We had the dot-com bust. The 2000 US election with its hanging

chads. 9/11. History hadn’t ended. Environmental problems got real. The

invasion of Iraq. Everybody tried to be GW Bush’s BBF. House prices doubled and

doubled again. Capitalism ran amok.

But for just

over 10 years, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to 9/11, the world was great

and we were all in its amazing center. I look at today’s twentysomethings and

it’s true that they’ve got cheap flights and dirty burgers and craft beers and the

internet on their phones and social media. But I wouldn’t swap places with

them. In fact, unless the remaining of the 2010s have an incredible surprise up their sleeves, the Nineties will have been the best decade of the last 50 years. We had it so good.

Comments

Post a Comment